The Shannon Airport cafeteria. St Valentine’s Day 1991. It was my first meeting with Brian Keenan. I was here with my documentary film maker colleague Mike Grigsby, with whom Brian had been discussing the idea of a TV drama documentary about his ordeal. I’d recently been selected as one of our supposedly ‘most promising’ new screenwriters and Mike wanted me to feel out the possibilities in Brian’s story.

Six months earlier Brian had been released after 4 1/2 years captivity in Lebanon as a hostage of Muslim fundamentalist militias, who had kidnapped him in 1985 when he was working as an English teacher in Beirut. At a memorable press conference after his return to Dublin he had described with haunting eloquence the mental and physical travails of himself and his fellow hostages. His poignant account of the special relationship he had developed with British reporter John McCarthy, with whom he had shared almost his entire captivity, had captured the public’s imagination. At the time of our meeting John was still incarcerated and it was to be another seven months before he, too, would be released.

Brian had filled out from the thin, drawn figure whom I had seen 6 months earlier on his televised return from his long captivity in Lebanon. His green eyes, sensitive, watchful and profound, were striking. He was soft spoken and weighed his words carefully. He was clearly not a man to be trifled with; indeed there was something of a pressure-cooker feel about him that put you immediately on your mettle. I told him that I wasn’t prepared to undertake on any kind of work that would be racist or demonising towards the Arab world. He was gratified by this. During their incarceration together he and John had often discussed the possibility of a film about their story - John had jokingly wanted to be played by Eddie Murphy - and they had always shared a similar view on this question. This early understanding between us was an important bond. I proposed that we retreat somewhere where we could explore things in peace and quiet and “see what happens, fly blind”. Little did I know that Brian’s assent was to set me on a 13-year long, tortuous journey to bring his and John’s story to the cinema screen.

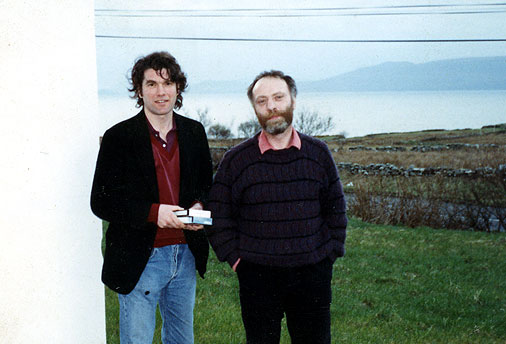

Two weeks later I was holed up with Brian in a remote, spartanly furnished bungalow which a local property man had lent Brian. It sat in the lee of Ireland’s holy mountain Croagh Patrick some eight miles from the local town Westport,County Mayo. We had no telephone, television or newspapers. Beyond the front sitting room window, by which I had a table and golfball typewriter, Clew Bay stretched idyllically towards the distant headland of Achill. There was a spiritual quality about this setting which helped put us at ease with each other in the journey of recollection which Brian was sharing with me.

With Brian Keenan in Co Mayo, 1991

Photo by suki dimpfl

During our first three days together preparing our workplace we had had a couple of lengthy, alcohol-fuelled but gentle conversations - one by candlelight in the old cottage to which Brian retreated from the frenzy of public attention that followed his release; another in a Marseilles-type seafront restaurant in Westport - in which we had already discovered an ability to speak very openly with each other. I’d brought a tape of Van Morrison’s ‘Poetic Champions Compose’ as an emotional and creative stimulant. Brian shared my love for the album, which had come out during his captivity. Morrison’s pained version of ‘Motherless Child’, so apposite to Brian’s description of his despairing moments when held in an isolation cell after his kidnapping, became a daily theme track.

Whenever we ventured out into any public place Brian, whose press conference had given him the aura of a sage, attracted endless well-wishers and equally endless free drinks. “Ireland needs a hero” he shrugged to me. During our restaurant conversation he had said to me; “You’re the first person I’ve listened to since I got back...”, a telling statement of how demanding the pressures of being this kind of celebrity were on him. He was in constant demand and would do anything that might help the release of the still held hostages. Their plight, exacerbated by the then current Gulf War,weighed heavily on him.

During our working spells Brian paced around the living room resurrecting his experiences in response to my probings. I stopped him every few minutes so that I could winnow out the key incidents and elements I needed to make the written outline I was composing work dramatically. His recall was wonderful and he had an immediate understanding of what I was looking for and why. A truth seeker, he made me feel comfortable asking the most searching questions, to which he responded with unflinching directness. He also had an artist’s eye for the revealing detail. Moments from his past and the feelings behind them, whether from his Belfast childhood or from the hellholes of Lebanon, sprang vividly from him.

It soon became apparent the treatment was the stuff of cinema, not television, and Mike Grigsby graciously acceded to this. The dramatic structuring and cinematic transposition of Brian’s recollections progressed smoothly. The creative process seemed to be of some therapeutic benefit to him too. I noticed that he was sleeping better and seemed more settled. Six weeks after we’d started ‘flying blind’ together, we had a lengthy completed film outline. It was to bring tears many of its readers’ eyes, including John’s when Brian first showed it to him later. We parted wistfully, knowing that we had shared in something special.

On holiday at a remote North Devon pub in August 1991 my wife and I watched the TV news of John’s release with exhilaration. I wasn’t surprised by how well John looked. I knew from Brian how the captors fed, even suntanned, their prisoners prior to release.

With John’s blessing to Brian for the film project, now titled ‘Blind Flight’, I was soon able to get Channel Four supremo David Aukin’s backing. Brian had meanwhile had his memoir ‘An Evil Cradling’ published to great critical acclaim and No 1 bestsellerdom. Back in Westport he and I fleshed out my outline into a biblically long first draft script, whilst John saw out the publication of his and Jill Morrell’s own account of their hostage years ‘Some Other Rainbow’. One of the script’s remarkable attributes was the unsparing honesty with which Brian was prepared to have his character portrayed in all its complexity and turbulence. Through it all shone a fierce independence of mind and spirit and a poet’s sensitivity and soul.

Ian Hart as Brian Keenan in Blind Flight

Photo by Paul Chedlow © Paul Chedlow / Parallax Independent

John joined us in July 1993 to become a full collaborator on the future development of the script. ‘Some Other Rainbow’ was heading the hardback lists, whilst ‘An Evil Cradling’ was top of the softback lists - the combined sales in the UK and Ireland would eventually amount to over 1.5 million copies. I was now in the unique situation of working with two No 1 best-selling authors simultaneously. This was also the one occasion when Brian and John could relive their ordeal together rather than separately as they’d had to do when writing their books.

For me the prospect of working with them as a duo was exciting but also tinged with apprehension. Having enjoyed a close relationship with Brian as his confidante since John’s absence in Lebanon two years earlier, would I now feel myself somewhat sidelined as they revisited their intense ordeal together for the first time? They soon put my worries to rest, with John proving as open and unsparingly honest as Brian. They compared notes on their experiences uncontentiously, and the main difference in perception that I noted was that Brian had always described their bonding as occurring within a very few weeks of their first meeting in captivity. But for John it took a year and a half before he could actually feel relaxed and confident in his cell mate’s company.

Linus Roache as John McCarthy in Blind Flight

Photo by Paul Chedlow © Paul Chedlow / Parallax Independent

I’d met John a couple of times before but this was my first opportunity to really get to know him. I’d always pictured him as tall whereas in fact he was slight. His soft brown eyes moved easily from humour to profundity and could also suggest hurt. I saw them sparkle as he bantered with Brian and turn pebble-hard if offended - his moral compass as unswerving as Brian’s - and he clearly had highly developed antennae for the sham and the ridiculous. He was beautifully mannered and sensitive to others’ feelings, with a wonderful enthusiasm and generosity of spirit.

One could see why his older fellow hostages came to so admire him, how he could have come, during his captivity, to epitomise Hemingway’s “Courage is grace under pressure”. He made one feel safe with him and also protective towards him - his modesty and lack of self-interest at times a cause for concern. He and Brian could hardly have been better cast together as “cell mates and soul mates”.

Being with them together as they mixed levity with deep seriousness gave me a strong sense of how their partnership worked in captivity; one could sense how each would be strong for the other at times of vulnerability and despair and how bracing humour and goonish fantasy sustained them. John had a quick understanding of screenwriting’s demands and its need for great economy of exposition, a legacy of his background in journalism. Like Brian he seemed to find sharing the experience with an outsider cathartic and was later to say; “At times it was so intimate that it felt like having a third character in the cells with us”.

By January 1994 we had a completed screenplay, Channel Four were deeply committed to the project and hopes were high. I was the film’s producer and we approached the cream of directors - Stephen Frears, John Boorman, Louis Malle, Nic Roeg and others - but without success. They either had preferable commitments, couldn’t see how to handle two men in small rooms, or else felt the script’s vision was too singular for them to find a way in for their own directorial sensibilities. Only the bright new hope of British cinema Danny Boyle and the veteran Roman Polanski were drawn. But they eventually withdrew - Boyle had another more immediately attractive venture ‘Trainspotting’; Polanski’s backers for ‘Blind Flight’ quit the film business and he had to move on.

Without a director we couldn’t approach actors. And without actors we couldn’t develop a cast ‘package’ to attract production finance. We remained in Development Hell. Two factors kept me going. Firstly, we had a great story and a script that still made a deep and moving impression on most of its readers. Secondly, I had a strongly supportive ‘family’ around the project - my co-producer Luke Randolph, my script and production consultant Archie Tait, my agent Elaine Steel and my wife. We reworked the script to try and make it more directorially appealing and trawled through the first rather than the premier division of directors.

However Channel Four finally felt unable to continue their support and even John, a constant source of encouragement, found his natural optimism hard to sustain after more than five years’ fruitless pursuit of a director. Brian’s interest had waned and I knew anyway that he’d long harboured an all too understandable ambivalence about having his life and character exposed to the fleeting and potentially diminishing nature of the big screen. By the summer of 1999 I was resigned to the likelihood that ‘Blind Flight’ could soon end up a stillborn dream.

A chance meeting with a cinematographer friend John de Borman and his suggestion that I direct the film reignited the project. Brian, John and my other colleagues welcomed the idea and I readily jumped at the opportunity. With the director question resolved I could at last approach actors and we soon had a ‘package’ of Joe Fiennes to play John and Ian Hart to play Brian. Experienced low-budget producer Sally Hibbin took over the production and, after a successful directorial test shoot containing impressive performances by the two actors, managed to piece together just enough money for us to make the film. A venture that had started in the shadow of one Middle East conflict, the 1991 Gulf War, was coming to fruition in the shadow of another, the looming invasion of Iraq. Unfortunately the latter prevented us from getting the final wriiten authorisations we needed to proceed with filming in Lebanon and we were forced to quit Beirut and its irreplaceable locations, with their blitzed out relics of the Civil War, a heavy blow but one to which one was inured by then.

working with linus roache

Photo by Paul Chedlow © Paul Chedlow / Parallax Independent

Finally to have two actors in front of me playing the people who had occupied my imagination as well as my life for so many years was the proverbial dream-come-true. In Hart and Linus Roache (Fiennes had dropped out because of other commitments) one had men of great emotional intelligence and intuition who shied away, as I did, from over-detailed analysis and explanation. I simply pointed to certain sense impressions I’d formed from Brian and John - like a sense of bereavement that I imagined came with the shock of suddenly being sundered from loved ones and thrust to the edge of human existence. Brian’s and John’s encouragement of Hart and Roache to make their own interpretations of their characters and their great openness was an important confidence builder. Maintaining that kind of openness between me and the actors during the shoot was equally important. As a director I often felt very exposed and vulnerable, and it was good to share that with those in front of the camera who had to be the most emotionally naked of all.

Hart and Roache, also physically near-naked most of the time on camera, had the added challenges of maintaining their energy levels and focus whilst subsisting on a meagre protein-only diet designed to keep them in an emaciated state - and having to perform at times in freezing conditions due to the vagaries of the production heating. I was particularly gratified when Roache exclaimed one day near the end of the shoot: “I’ve never made so many mistakes before!” I’d encouraged all the actors, including the mainly non-professional Lebanese who played the captors, not to be afraid of making mistakes; “I’ll make twenty times more than you ever will!” had been my exhortation to them before we started shooting. Having the confidence to risk getting things wrong seemed to me a vital part of of the creative process, as did trying to stay sensitised to one’s deep down instincts, not easy for actors or directors in the highly pressured hustle and bustle of of a film set.

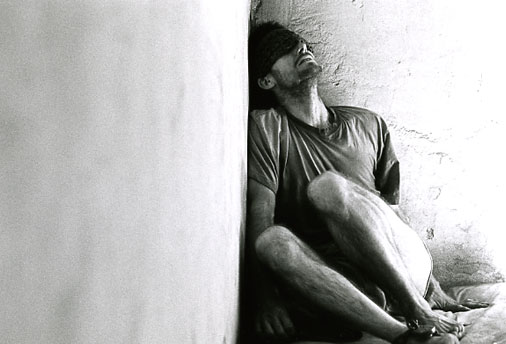

It was as important for the actors as for the look of the film that the sets be as brutally realistic as possible. Our designer Andrew Sanders used breeze blocks and other solid materials, with dilapidated and dank finishes, to make them authentic to the actors’ touch as well as to their senses.

ian hart resting during filming Blind Flight

Photo by Paul Chedlow © Paul Chedlow / Parallax Independent

Because of the acute lack of time and money I had to shoot the film in the simplest, sparest way guided by our cinematographer Ian Wilson, who knew exactly what I meant in my references to two inspirational directors Ingmar Bergman and Robert Bresson. My mantra was ‘trust the story, trust the characters, trust the actors, trust the audience’. I survived on two hours sleep a night, bouyed up by the actors’ and crew’s support for the novice in their midst.

Our 6-week shoot in Belfast, Glasgow and Tunisia in early 2003 culminated with a scene of the three young Lebanese guards on whom the film’s dramatisation centres watching their charges being taken away from them by other militiamen. They managed very well to convey their characters’ awkwardness, uncertainty and sense of loss, those humanising elements which had always been essential for Brian, John and me. They’d proved remarkably adept at giving naturalistic performances foreign to their own culture’s more theatrical acting habits, aided by Hart’s and Roache’s generous camaraderie and encouraged by the lead actors’ dictum “We all make each other good”.

During the editing I was enveloped by post-natal depression about my work, a normal occurrence for a director I was told. It was only when I viewed the final print from the laboratories, with all my creative colleagues’ work - acting, cinematography, sets, sound track, music, editing - shown to their full advantage, that this lifted. John and his wife Anna viewed the film privately and we had lunch together afterwards. Both of us were mentally rubbing our eyes, still not quite believing ‘Blind Flight’ had finally happened. But it was evident from his and Anna’s responses that the film has greatly affected them. The scene in which he is shown a video of his mother’s appeal to the kidnappers for his release was particularly powerful for John; “That was just like it was!” he exclaimed. I was a little startled, being so conscious of the inevitable gap between what actually happened to him and Brian and its filmic interpretation. More startling was another quiet observation: “You know, that’s the first time I’ve ever seen the guards...” An absolute rule during their long captivity was that they had to don their blindfolds every time any of their captors entered their cells.

Last September, almost thirteen years since I started out ‘flying blind’ with Brian, over four hundred turned out for the inaugural friends-and-family screening at the Chelsea Cinema. John and I sat together apprehensively. Our nerves quelled at the amount of laughter in the auditorium and the buzz afterwards. “It was worth the wait!” was a particularly pleasing comment. It wasn’t until the film’s premiere in February that Brian and his wife Audrey were able to see it on a big screen and experience for themselves the buzz of an appreciative audience. He gave me a huge hug reminiscent of the kind we’d had when we’d finished the original outline together. As any decent scriptwriter knows, it’s what can be said without words that matters.