Looks that Kill - History

From the outset I wanted the film to try and convey the emotional impact of BDD on a sufferer. I wanted it to have a personal feel and not be ‘medicalised’.

I was under no illusions as to how hard it would be to find a sufferer who would be willing to be filmed. As world leading BDD specialist Dr David Veale at the Grovelands Priory Hospital in North London pointed out, the idea of being seen on camera for somebody obsessed with their ‘hideousness’ would probably be insuperably daunting.

But he agreed that my own personal experience offered a ray of hope – I could possibly bridge the crippling shyness, loneliness, sense of alienation and terror of the normal world that a BDD sufferer endures. He had a young woman who had recently come into his care after almost killing herself with the savagery of her arm slashing. He’d mention me to her.

Weeks passed by as 1999’s Spring turned to Summer and Dr Veale’s prognosis looked all too correct. Then out-of-the-blue on a July morning I got a call from his patient 21-year old Gail Bettinson. It was an electrifying conversation for both of us, the first time either of us had found a fellow sufferer to whom we could confide. For 1 ¼ hours we talked like old friends, in one leap transcending age, sex and class as we exchanged intimate details of our BDD experiences, still vividly memorable for me.

A particularly potent memory was how the sufferer’s extreme sense of physical alienation from the normal world extended to an estrangement from one's own past and to any conceivable future, leaving leaving one trapped in a despairing perpetual present (this memory would inform my dealing with later projects like Living On The Edge and Blind Flight).

Gail was due to visit Grovelands Hospital a week later to see Dr Veale. To my surprise and gratification she not only agreed to the idea of appearing in a documentary by me – she was keen to help fellow sufferers – but also to me filming her session with Dr Veale as ‘pilot’ material to help raise TV interest in the project. From her voice, with its gentle Suffolk burr, I imagined an apple-cheeked young countrywoman. How wrong I was!

Through the Hospital’s Roman column-flanked entrance came a very pretty girl in a black mini-skirt and chic blouse. She had big, open eyes, heavy make-up and numerous piercings including in her tongue and navel – I was to learn that these were designed to draw attention away from her nose and her chin, the two features that caused her the most particular self-revulsion.

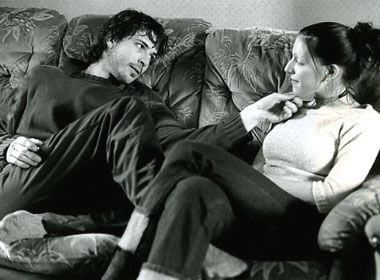

Accompanying her was her shy boyfriend Darren, as

darkly handsome as a young protagonist in a Pasolini movie.

As we filmed her session with Dr Veale it was immediately apparent to Roger Graef and I that Gail, with her disarming candour and articulacy and enormously appealing personality, was a gift as a subject. Afterwards I volunteered to be filmed by Roger chatting with her about our respective BDD experiences. It seemed only too right that I, too, should be an on-camera participant given the courage she was showing in letting us film her.

Two weeks later I went to Gail’s hometown of Lowestoft with Alan James, Roger’s cameraman of choice for particularly sensitive observational situations, to gather more material for the pilot. My plan, openly discussed and agreed with Gail and Dr Veale, was to use the presence of a film camera as an adjunct to her Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. This involved her having to expose herself on a day-to-day basis to people and situations that triggered her acute anxiety states and panic attacks - walking out in the town, visiting a pub, reducing her make-up. Being filmed doing this would be a big added challenge.

Gail gave us extraordinarily intimate and touching material - her long, obsessive make-up rituals and multi-mirror body examinations in preparation for facing her daily world, at times almost prayer-like in their constant repetition, at other times unnerving in their fearfulness and panic. She exposed other obsessive compulsive behaviours, like her hoarding of empty beauty product containers, likening them to her “babies”, and vividly demonstrated her use of kitchen knives for anxiety-relieving self-mutilation.

Back in David Naden’s cutting rooms in Soho, a last bastion of 1960’s radical filmmaking, Dai Vaughan, one of the most eminent British post-War documentary film editors, cut the rushes into a 5-minute pilot. Our material, compiled in only three days, was to form a major part of the final 50-minute documentary commissioned three months later by Olivia Lichtenstein, overseer of the prime BBC1 Inside Story series.

The project progressed rapidly and my old sound recordist colleague Mike McDuffie joined Alan James, our production co-ordinator Chloe Kidel and me for two short filming periods in late November and late January. Their gentle unobtrusiveness was vital in helping put Gail at her ease. By early February 2000 we had a wealth of very moving material featuring not only Gail but also those closest to her - Darren and her family - for whom Gail’s condition was a source of massive strain.

I did some more filming of me with Gail discussing the problems involved in exposing herself on camera as part of her therapeutic process. Gail was growing in confidence, now visibly transformed as a young woman able to successfully confront her fear of singing in public at a local pub karaoke competition - with our camera trained on her. Our work with her climaxed with her finally able to fulfil her dream of being successfully auditioned as lead singer for a local band.

Though working with Dai Vaughan was constantly inspiring – his sensitivity and feel is that of a real filmmaker's whose references come as much from cinema as from documentary - the film's editing was ultimately less happy than its shooting. In the now ratings-driven climate Dai and I had to adjust to the filmmaker’s declining power in the creative process in the face of TV executives’ editorial primacy and the now standard insistence on a ‘user-friendly’ commentator. But Roger did manage to persuade Olivia Lichtenstein that I should be the audience’s hand-holder, with an exhaustively checked commentary to voice.

Most regrettably, we had to trim out material of Gail’s and my first encounter at Grovelands Hospital, with its highly unusual immediacy of relationship between filmmaker and subject central to the film’s realisation, in favour of more family material as the Beeb wanted to attract a family audience.

Looks That Kill was transmitted on BBC1 Inside Story on March 7th 2000 at 10.00pm, a post-‘watershed’ slot when ratings plummet. Despite that, and having to compete with a European Cup tie between Manchester United and Bordeaux, the programme attracted 4 million viewers, a very big audience for a ‘serious’ documentary.

The BBC’s Helpline received “a huge response” of over 8000 calls, the second largest in its history, a Helpline executive told me. Callers included “a great proportion from people thinking that they might be suffering from the condition…many mothers with concerns about their daughters, but sons also a concern.” The National Phobics Society reported over 2000 calls within 48 hours of the film’s transmission and “as a result of this wonderful response” (!) its setting up of nationwide support schemes for BDD sufferers.

The statistics for sufferers of this hitherto little known disorder were startling. BDD was estimated to affect some 400,000 in the UK (5 million in the USA and millions more worldwide), evenly distributed between males and females. Suicidalism was exceptionally high, with 1 in 4 attempting suicide and 10% of them ‘succeeding’.

It remains hugely gratifying to know that I made a film that helped relieve the suffering of many, possibly thousands, including Gail, whose visible progress is evident in the programme. And that from the statistics it may well have saved a number of lives.

Despite audiences of 3-5 million the Inside Story series was taken off the air by the BBC soon after Looks That Kill’s transmission, a further sign of the shrinking horizons on mainstream television for more serious documentaries at the time.