Living on the Edge - History

![]() LOTE (Living On The Edge) is an outstanding attempt at engaging with contemporary reality through a documentary language which draws deeply on the work of the past as well as pressing forward to new connections and combinations.

LOTE (Living On The Edge) is an outstanding attempt at engaging with contemporary reality through a documentary language which draws deeply on the work of the past as well as pressing forward to new connections and combinations. ![]()

JOHN CORNER, THE ART OF RECORD 1996

My contribution to Living On The Edge as Mike Grigsby’s creative collaborator sprang from an unrealised project of mine from the mid-1970’s The Struggle For The Land about the colonisation of the Countryside by the City both socially, economically and culturally for which I had composed a collage-style narrative and had shot pilot material. (See Monthly Film Bulletin, June 1987)

It was centred in North Devon, the locality of generations of my Furse family antecedents and an area whose still living ties to its past remain beautifully evoked in photographer James Ravilious’ classic work of the period for The Beaford Archive.

With its then impending ‘opening up’ by new motorways and high-speed train services, in addition to the already pervasive effects of the mass media, it was clear that the area’s history, culture and identity were facing massive dislocation. I wanted to convey the conflict between the old and the new and the fracturing of its rural people’s own sense of their history that this involved.

My project was inspired by the social historian Raymond Williams, particularly his book The Country And The City, by the oral historian E.W. Martin a local Devonian, and by visionary Bristol independent filmmaker David Hopkins. (See Acknowledgements).

I had come to meet David through a shared interest in new technologies, particularly home movie and newly available video equipment like the ‘portapak’, and how these could be used to develop work and production processes alternative to the mainstream.

In the 1970’s public funding bodies on whom independent filmmakers then depended, like the BFI and the Arts Council, had become heavily influenced by the prevailing issue of ‘structuralism’ and the decoding of film language. Like David I felt that this was creatively inhibiting. The Struggle For The Land was an attempt to develop a film whose language would play with the norms of how daily reality and history are ‘sold’ to the public by by the media structures - whether in news, documentary or other ‘natural’ forms - mixing elements drawn from popular culture like soaps with which audiences could easily identify.

In my project local working people would give their own ‘unofficial’ view of the history that had shaped their present and sense of the future, in the face of the ‘official’ versions of the nation’s history as portrayed in TV, newsreels, archives, advertising and popular culture. The participants’ ‘unofficial’, living-memory history was to be constructed as a linear narrative from the First World War to the present within the collage.

I saw Living On The Edge as an opportunity to use this approach effectively and also to extend The Struggle For The Land’s Country and the City themes in a filmic way by intercutting the rural with the urban, a montage I was already using in a fictional screenplay. I also suggested we use extensive music from different eras, both popular and ‘street’, to assist and counterpoint the narrative - for both Mike Grisby and I the use of commentary was anathema.

These ideas chimed with Mike feeling at the time a need to progress his filmmaking, so it was a happy congruence. An outstanding exemplar of John Grierson’s dictum of documentary as ‘the creative interpretation of reality’, and long inspired by Humphrey Jennings’ hugely inventive and poetic work, Mike saw Living On The Edge as an opportunity to extend his palate. He cited Jennings’ Diary For Timothy as a paradigm, which I hadn’t seen, and directly quoted from it in a scene in the final edit.

I also felt that this cinematic approach could attract interest in its screening in art-house cinemas, a groundbreaking departure for a network TV documentary. Archie Tait, the Director of the Institute Of Contemporary Arts (ICA) Cinema, was keen to exhibit the final film and the British Film Institute (BFI) eventually came in with funding for a 35mm blow-up from its 16mm TV format.

Mike always insisted on lengthy research to build trust and understanding with his films' subjects. Unusually among documentary directors he entrusted the main research to his researchers rather than burying himself in the process, using his keen intuition and judgement to assess our work during visits in the field.

The nationwide scale of the project and its open-ended and demanding nature required a resourceful research team. Mike recruited Central TV staffer Catherine Bailey and freelancer and former social worker Sara Tibbetts.

Mike journeyed around the country getting a sense of peoples’ feelings and the film’s potential imagery, and researched possible music for its narrative. I co-ordinated the research in the field for its participants and settings and short-listed potential ‘cast’ with Catherine and Sara prior to Mike and I making the final selection.

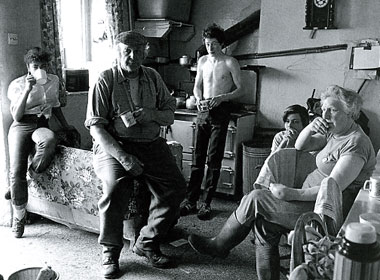

Over many months of grassroots work and trust-building Catherine and Sara trawled some of the most economically threatened and deprived neighbourhoods in Britain. The sense of fragmentation and apathy Mike, Catherine, Sara and I all found, engendered by Thatcherism’s successful assaults on the unions and by the debilitating effects of economic globalisation, was depressing.

Particularly shocking was the way that many respectable working people - the kind heralded in the War and its aftermath but now ‘ducking and diving’ to survive in a hyper-consumerist society where the rich were getting richer and the poor poorer - had become effectively criminalised. Their loss of pride was often palpable.

Amongst Mike's many strengths is his consistently positive attitude and he kept us all buoyed up during the many research months. Catherine and Sara found excellent participants for the film in the Welsh coalfields facing closure and in the ‘sink’ estates in Scotland and Merseyside with, as one put it, their "non-working class” communities.

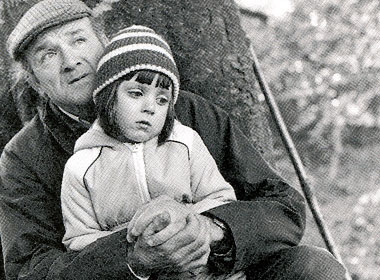

A Devon solicitor John Burnett gave me access to the secretive world of farmers facing bankruptcy, where exposing their situation could accelerate their predicament and where depression and suicide were uncommonly high. Through John I found a bankrupt farming family the Rolfes whose story was to become central to the film.

Frank Rolfe, a tall, strongly-built countryman whose sad-eyed, stoic dignity and quiet thoughtfulness reminded me of Henry Fonda in Grapes Of Wrath, had worked his way up from being a young agricultural labourer in Oxfordshire to owning a small farm near Dartmoor. Now, thanks to forces beyond his control - the EU milk quotas; the demands of the banks - he was facing the ruin of his boyhood dreams.

By the time of filming in Autumn 1986 I had experimented with written collage work for the film’s realisation based on all our research and culled imagery and had developed a loose narrative structure. With Catherine and Sara’s help I could formulate the questions and themes that I was to raise with the participants during filming to prompt their spoken material from which the narrative was to be constructed.

This technique, which involved setting up dialogue scenes with the participants talking between themselves on themes agreed with them, rather than being interviewed, made for a less obviously controlled, more ‘naturalistic’ exposition. Mike and I also welcomed the participants’ own ideas - indeed the very moving climactic scene in which the Rolfes’ daughter Alison reads her brother’s requiem to their farming life to their tearful parents, was initiated by Frank himself, who volunteered the poem shortly before we shot the scene. That he knew its reading would be emotionally demanding was evident when he first showed it to me, and his and his family’s courageous commitment to proceeding with the scene was an example of the benefits a film’s true-life subjects’ participation in the creative process can bring. (see Screenwriting/True Stories)

Whilst I concentrated on the content, themes and narrative points of the dialogue scenes and the structural ‘scripting’ Mike focussed on the directing. As usual he used highly gifted, creative technicians - Ivan Strasburg and Tom McDougal on camera and Mike McDuffie on sound (Ivan and Mike McDuffie had also worked on A Life Apart). Like the best directors Mike communicated the sense of what he was after so strongly that they all produced material imbued with his sensibility.

Mike also had an outstanding Central TV editor Julian Ware. Whilst my main responsibility was helping clarify the structure of the shot material, and Julian and Mike drove the research for suitable counterpoint material (newsreels, ads, movie and radio excerpts, music etc), open as ever to ideas from the team, Julian brilliantly developed and synthesised the film’s complex, multi-layered form.

ICA Cinema Director Archie Tait undertook Living On The Edge’s cinema launch at the ICA in May 1987. The film was transmitted nationwide as a Central TV Viewpoint programme on November 10th 1987.