DIRECTING / ACTORS

I’d always admired the public nakedness involved in actors' work and the courage that this takes. What I hadn’t appreciated until directing my debut feature film Blind Flight is the nakedness of the director!

For me fear and tension are the enemies of intuition and creativity and I felt it was essential to create an atmosphere where the actors and I could feel safe - safe to not know the answers, to make mistakes and try again, without inhibition.

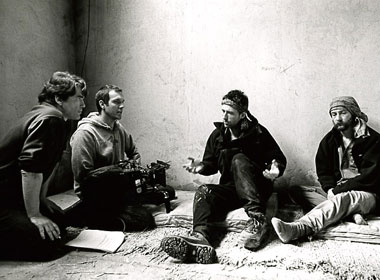

That’s why the chemistry of the crew is so vital. My producer Sally Hibbin provided me with a wonderfully supportive unit, with 1st Assistant Director Charlie Leech, Director Of Photography Ian Wilson and Designer Andrew Sanders the fulcrum of its 'family' atmosphere.

This helped the actors and me have a space where we could be as in touch with our instincts as possible, something hard enough in the noise of everyday reality let alone in the hustle of a film shoot.

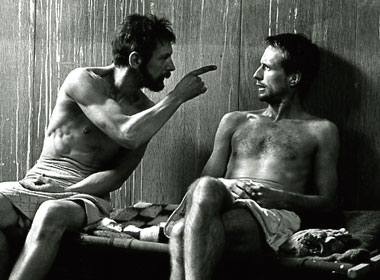

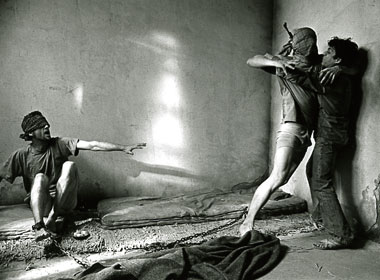

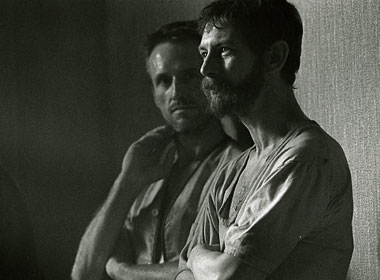

The story required a sense of exceptional intimacy between two males in close confinement, attuned to each other’s slightest nuances (see Home page). For this I needed a very quiet set where low-key communication between me and the actors could help their tone and focus - actors, like writers, are porous and can pick up on anything, including a director’s expressiveness.

If theatre acting has an element of the kid performing to please its parents and peers, then screen acting is what the kid does when it thinks nobody is there, nobody is watching. It's the intense, private and mysterious world of the human being that I wanted to convey, on which the audience becomes an invisible eavesdropper - an intention as applicable to documentary as to drama (see: Film Clips for Blind Flight and documentary Looks That Kill).

I wanted the performances to be as spontaneous as possible, with rehearsals kept to a minimum. The actors felt comfortable with this. Ian Hart (Brian Keenan) and Linus Roache (John McCarthy) gratifyingly said that their needs were “all in the script”.

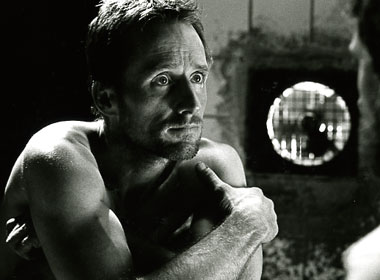

I'd written the sets as metaphors for stages in the two captives' journeys, with the film to have the heightened sense of reality that they had experienced. Andrew Sanders' superbly authentic work, using solid materials and dilapidated finishes, together with Ian Wilson's richly atmospheric lighting, were vital to achieving this. The realism made a big difference for the actors and me, and indeed made an impact on everyone on set.

It was extremely important that the actors felt as free as possible to make their own interpretations of their characters, without feeling imposed on by the fact that, as writer/director, I had a very clear vision of the characters and the scenes. Brian (Keenan) and John (McCarthy) were also very generous on this with Ian and Linus. (see Screenwriting/True Stories)

I let the actors find for themselves the most natural ways of working with each other. Ian Wilson and I then constructed the shots around them. Ian was adept at ‘master’ shots that incorporated the action and key scene points in the most economic way, whilst allowing the actors maximum freedom of movement. We made minimal use of ‘marks’ for them to have to hit for the camera - I wanted the actors to work as ‘unconsciously’ as possible.

In casting I knew within nanoseconds of meeting them that the actors were absolutely ‘right’ for the parts, even though they didn’t physically resemble them. Ian (Hart) had the habitat of the City about him, edgy, constantly on the alert for danger around the next street corner. Linus (Roache) was the Country actor, still, watchful, scanning distant horizons for potential threat - the perfect yin to Ian’s yang, like John’s to Brian’s. Among major stars Al Pacino and Clint Eastwood are embodiments of the City and the Country actor.

Screen acting can be an art in its own right, exemplified in Liv Ullmann’s and Bibi Andersson’s hypersensitive performances in Ingmar Bergman’s ‘Persona’, which were a model for the kind of transparency of acting I was seeking.

The sparse simplicity of ‘Persona’ and Robert Bresson’s ‘Diary Of A Country Priest’ was also inspirational given the acute shortage of time we had to cover all the scripted scenes - had Blind Flight been in black-and-white these directors’ influences might have been more obvious.

The landscape of the human face is endlessly fascinating and revealing and the use of big close-ups was an obviously effective way to convey Brian's and John's complex emotions, a demanding test for Ian and Linus. A camera monitor is seductive for a director - you can see exactly what the camera is recording. But this lacked engagement with the actors, so I stood by the camera in the traditional way, to be as close to them as possible.

During the ‘takes’ I kept a cupped finger around my right eye to shut out any distraction and concentrate completely on their faces. I felt that if their faces radiated their characters’ inner emotions truthfully, then their physical movements would follow suit. How they listened to each other was vitally important.

I didn’t feel comfortable with the abruptness of saying ‘Action!’ and wanted something gentler to help create the intimate atmosphere of the hostages’ confinement. Sally Hibbin gave me a good tip from her work with Ken Loach - to simply tell the actors very quietly “in your own time…” and leave them to start the scene.

I was aided considerably by the actors working as an ensemble, the more experienced Lebanese Ziad Lahoud and Bassem Breish helping the less experienced Mohamad Chamas, Dany El Khoury and Fadi Sakr, with Ian and Linus a constant source of support and encouragement - for me as the novice director as well as for their fellow actors. It's moving and impressive what inexperienced and non-professional actors can achieve if given the confidence, as the Lebanese actors' performances showed.

Blind Flight has been particularly noted for the quality of Ian's and Linus' performances. But as director I didn’t ‘get’ the performances. The actors gave them. I did learn, though, how much of a director’s value is in that moment when you make the decision on whether or not a take’s performance is ‘in the can’. It’s a totally instinctive decision, taken under enormous pressure as the clock and the till are constantly ticking.

I always checked with the sound recordist Stuart Bruce not simply for whether he'd got 'clean' sound but also for any comments he might have on an actor's delivery. A director has a lot to focus on during a 'take' but a recordist is purely concentrated on the quality and feel of the sound. The creative judgement of a sensitive recordist like Stuart or Mike McDuffie can be very valuable to a director, something often overlooked in documentaries as well as dramas.

I also always checked that the actors didn’t have any reservations. This wasn’t simply courtesy - it was an expression of my confidence in their innate artistic sense, with its ice in the heart that would tell them whether they had more to give.

Though the cast and crew had been a joy to work with, after we'd finished shooting I felt pretty depressed - the movie was so different from the far more cinematic one I'd had in my head for all the years of its gestation. But the impending occupation of Iraq had meant us losing the terrific, still war-scarred locations we'd prepared in Lebanon. And the lack of money had left no time for anything other than the sparest of filming coverage - an average of closer to 2 than 3 shots per scene. It was frustrating to feel that one was constantly rescuing the bare essentials of scenes rather than creating them as one had originally seen them.

Having to be so sparing in the shots to cover each scene leaves a director with nowhere to hide in the editing. But it's remarkable what a creative, independent-minded editor like Kristina Hetherington can do both to cover gaps in a film's original material (and directorial oversights!) and to add to a film's realisation - her use of special effects like slow-motion was one of her many significant contributions.

Music is all too often over-used and over-emphatic, simply underlining what should already be there in a film's drama rather than adding to the audience's experience of the film. Sound, on the other hand, and its wonderfully suggestive scope, is too often under-exploited. In post-production the film's gifted Irish team made any such concerns redundant. Composer Stephen McKeon’s haunting, beautifully judged Arabic/Celtic score, and sound designer Nicky Moss’ multi-layered, highly attuned soundscape, sensitively mixed by John Fitzgerald and Tom Johnson, added enormously to the film’s atmosphere and resonance. Working with them was a turning point in lifting my spirits. I could see that, whatever its shortcomings, the final film still contained the essence of what had always mattered to me.

As a writer you work from the inside out - a link you have with actors. As a director you work from the outside in. The challenge as a writer/director was to be able to move quickly and easily between these two poles, most particularly for the actors’ sakes. And to be receptive to colleagues’ ideas and to what was actually happening in front of one’s eyes, rather than being defensively stuck on the movie in one’s head or in one’s screenplay.

There are many directors who impose their will and their vision. For me, though, it's important to be really open in the creative process, to surrender, whether to one's characters in the writing or to the creative brew of working with talented colleagues who have an immense amount to contribute.

This can add immeasurably to a film's realisation as well as being fulfilling in its social creativity. It takes fundamental confidence in yourself, in the film you envisage, and in your and your screenplay's ability to convey it. But if the roots are strong, the tree can bend in many directions and still be the tree of your dreams.